[Sequence Log 005]

Even CrossFit Coaches

Get Injured

This week, I witnessed something that made me reconsider everything I thought I knew about injury prevention.

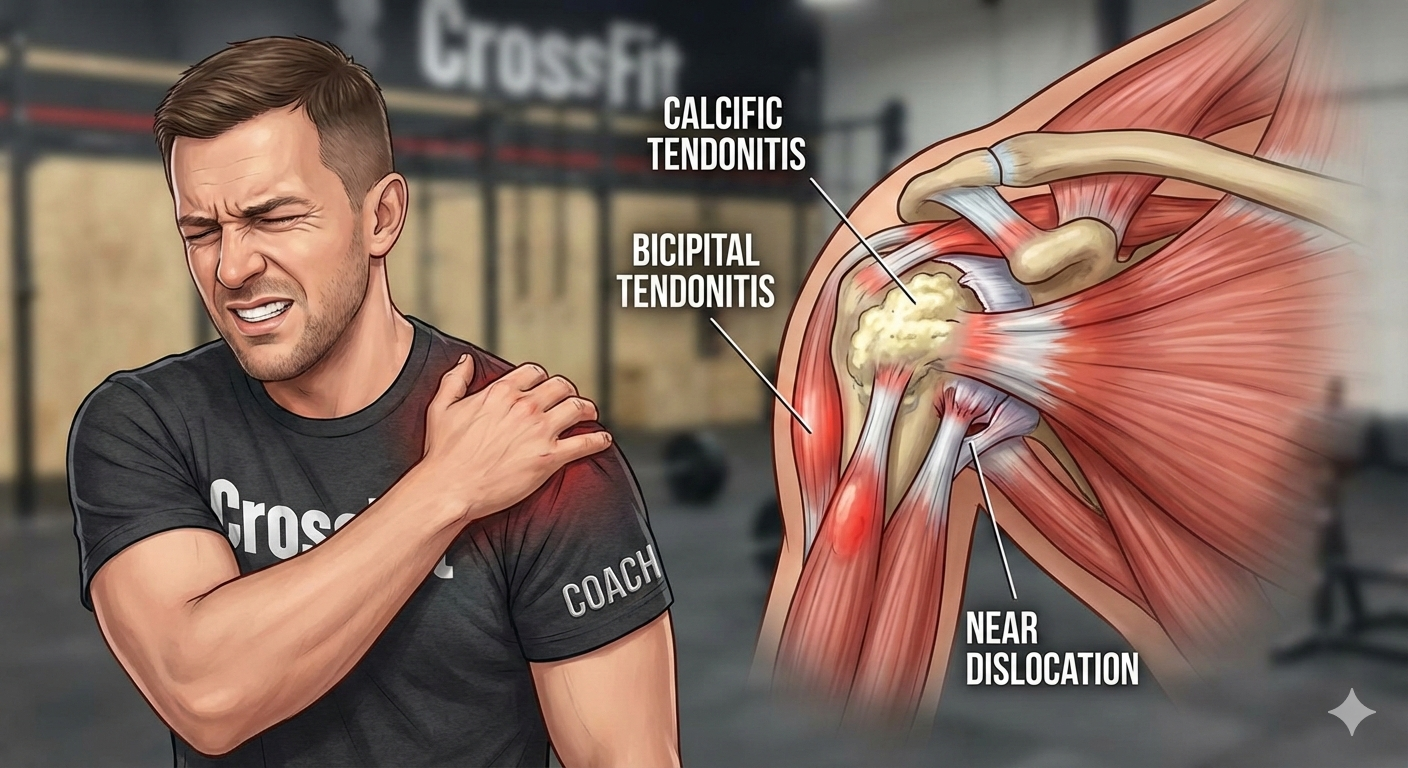

A coach at my box—someone with years of CrossFit experience, excellent performance, and extensive coaching credentials—suffered a serious shoulder injury.

It wasn’t a complete dislocation, but it was close.

The diagnosis: calcification buildup and biceps tendinitis.

What struck me most wasn’t the injury itself, but the circumstances.

1. The Coach’s Shoulder Injury

― Experience and knowledge don’t prevent injury

The coach had been aware that something was off with their shoulder.

They felt it wasn’t quite right, yet they continued to push through workouts.

- Ignored the warning signs

- Continued with heavy loads

- Maintained high intensity despite discomfort

The result: a near-dislocation injury that required significant recovery time.

This coach has:

- Years of CrossFit experience

- Strong performance capabilities

- Extensive coaching background

- Deep knowledge of physiology and movement

None of this prevented the injury.

2. Experience ≠ Injury Immunity

― The gap between knowledge and practice

This incident revealed something important:

Exercise experience and physiological knowledge

are separate from injury prevention and recovery management.

Knowing how to perform movements correctly doesn’t automatically mean you’ll recognize when to stop.

Understanding recovery principles doesn’t guarantee you’ll apply them to yourself.

The coach had always been someone who pushed for heavier weights and more challenging movements.

That drive—the same one that builds strength and skill—can also lead to ignoring warning signals.

3. The Need for Recovery-Focused Coaching

― Beyond movement instruction

This experience highlighted a critical gap in how we approach coaching:

- Movement coaching: Teaching proper form and technique

- Recovery coaching: Monitoring and adjusting based on recovery state

Most coaching focuses on the first.

But the second is equally, if not more, important.

We need coaching that monitors recovery,

not just performance.

This isn’t about being cautious or avoiding challenge.

It’s about recognizing when the body needs to recover,

and having the discipline to adjust accordingly.

4. My Personal Experience

― Adjusting after shoulder pain

Last week, I experienced shoulder pain during workouts.

Unlike the coach, I made a conscious decision to adjust:

- Reduced weight on shoulder-intensive movements

- Slowed down execution speed

- Intentionally prioritized recovery

This wasn’t about being weak or avoiding hard work.

It was about recognizing that injury prevention is the foundation of all goals.

If I get injured, I can’t pursue any goal.

No matter how ambitious the target,

an injury makes it unattainable.

5. Where Do We Set Our Goals?

― The cost of ignoring recovery

The coach’s situation made me think about goal-setting:

- Is the goal to push harder every session?

- Or is it to maintain consistency over the long term?

If we prioritize intensity over recovery,

we might achieve short-term gains.

But we also risk losing everything to injury.

If you get injured, you can’t achieve any goal.

That’s closer to failure than success.

The real challenge isn’t pushing harder.

It’s finding the balance between intensity and recovery.

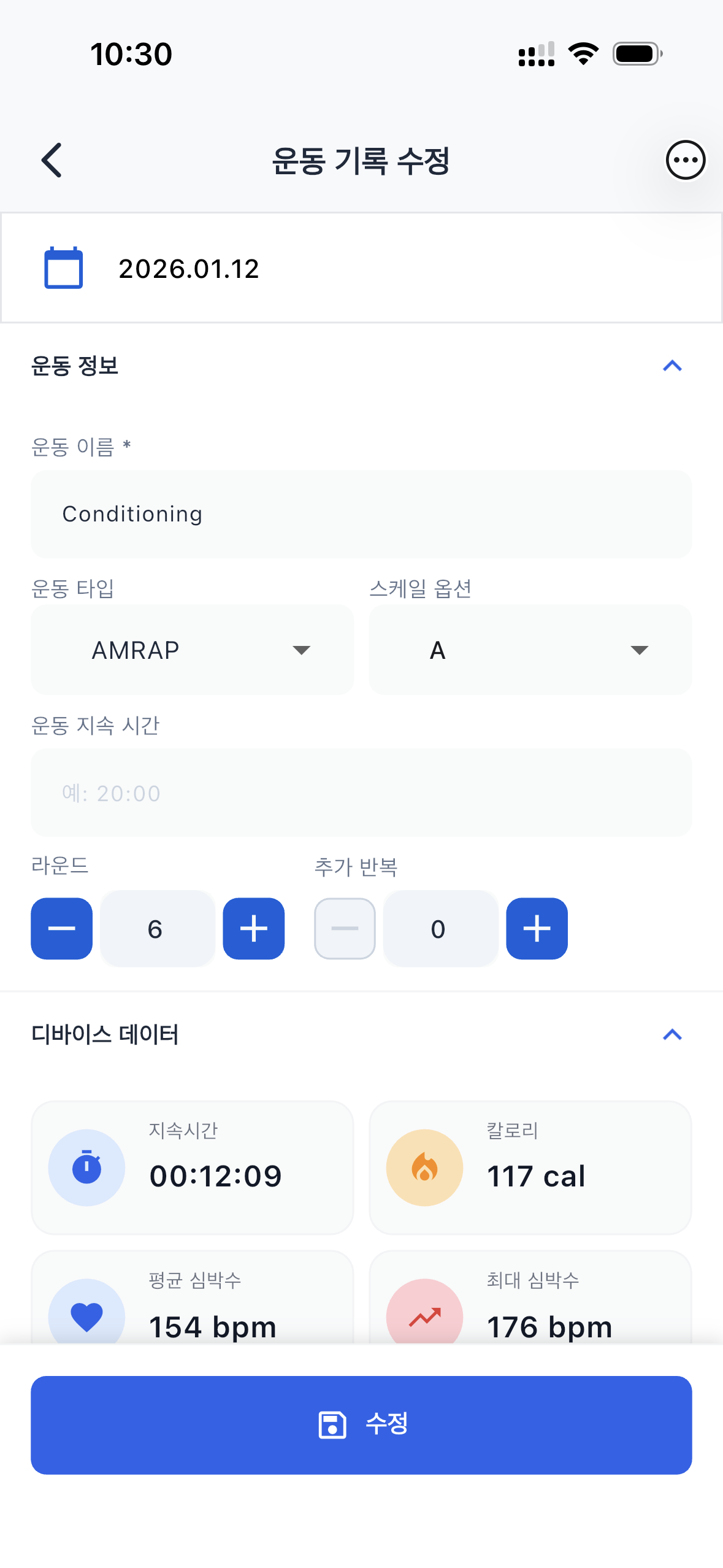

6. The Necessity of Monitoring and Coaching

― Measurable signals, not just feelings

This experience reinforced something I’ve been thinking about:

We need monitoring and coaching systems

that can detect recovery state objectively.

Not just subjective feelings of “I’m tired” or “I feel good.”

But measurable signals:

- Heart rate variability

- Recovery metrics

- Training load vs. recovery speed

- Daily activity patterns

The coach knew something was wrong,

but by the time it became obvious, it was too late.

What if we could detect these signals earlier?

What if we had systems that could warn us

before the body breaks down?

7. What This Means for Training

― A shift in perspective

This incident isn’t about being afraid of injury.

It’s about recognizing that:

- Experience doesn’t grant immunity

- Knowledge doesn’t guarantee prevention

- Recovery requires as much attention as training

The coach’s injury serves as a reminder:

even those who know the most about movement and physiology

can fall into the trap of ignoring recovery signals.

[Next Sequence]

This sequence started with a coach’s injury,

but it points to a broader question:

How do we build systems that prevent injury

while maintaining training intensity?

In the next installment, I’ll explore:

- How to design recovery-focused coaching systems

- What measurable signals we can use to detect recovery state

- How to balance intensity and recovery in practice

The next log will be

an attempt to integrate injury prevention, recovery monitoring, and training into one cohesive system.